Motives and Melody¶

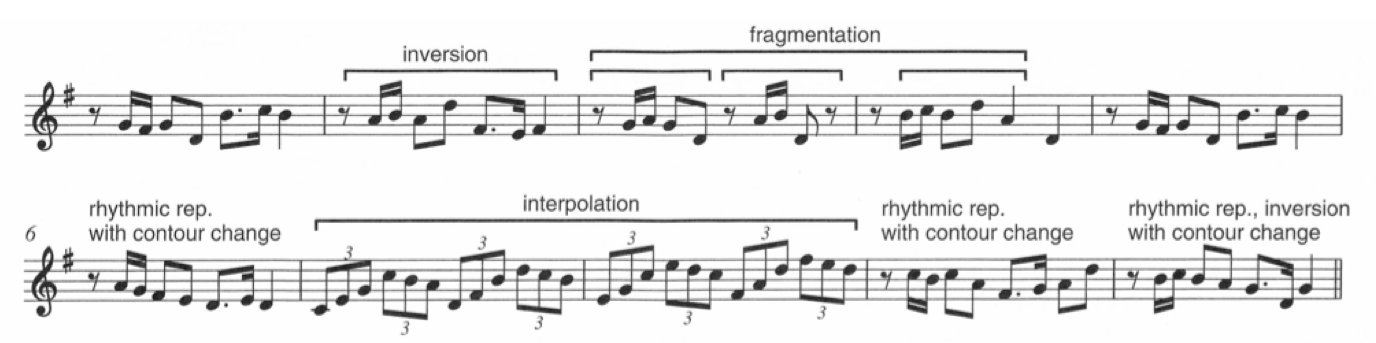

Developmental Repetition¶

Motivic repetitions whose pitch and/or rhythmic content are significantly altered. Although developmental repetitions may not be as audible as modified repetitions, they are often quite important, as they lead to growth in the composition, and allow for motion.

Single Interval Motives¶

Last week we saw an example of a single interval motive when we analyzed Debussy’s ‘Des pas sur la neige.’ Let’s look at another example of a single interval being used as a motivic device.

Note how Brahms doesn’t break the pattern of falling thirds, except once for range issues.

Melodic Writing and Analysis¶

Intervals don’e exist in isolation, but rather they function as part of larger musical constructs, such as a melody. Let’s listen to a few melodies and ask the following questions:

Is the melody in a key, how do we know, and why? Do the melodies have a specific shape or contour? What sorts of melodic intervals occur between pitches? Are there accented events in the melodies (such as instances that draw your attention, such as leaps, chromaticism, and longer durations? If so, are these events isolated, or does the composer prepare them in so way?

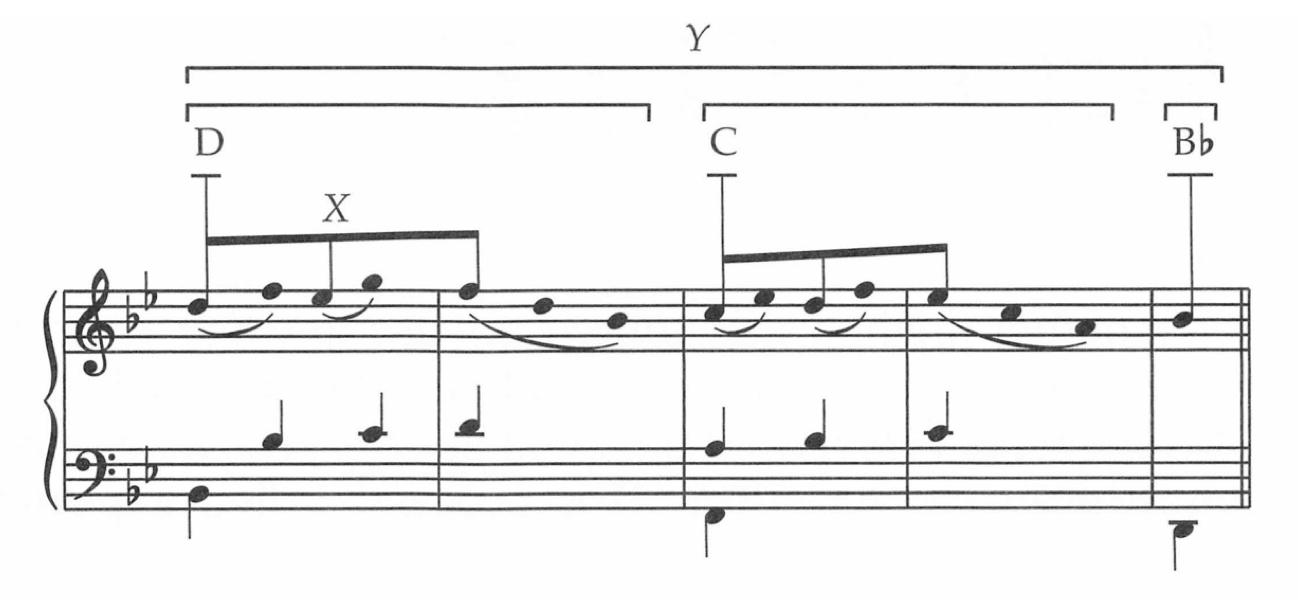

Melodic Reductive Analysis¶

Look for stepwise motion that connects the beginning of a phrase with its melodic cadence. Begin by labeling the scale degree of the melodic cadence. Identify the scale degree of the beginning of the phrase. Look for what we might call “structural tones.”

In the following example, we are able to see a structural descent of a third. The D on the downbeat, descends to a C at the onset of m.3, and B-flat on m.5.

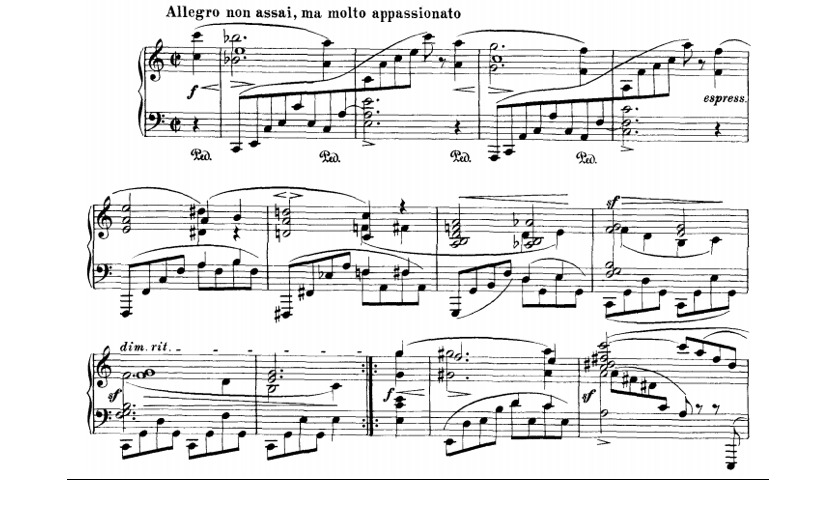

This can be elongated throughout a longer phrase. As we see in this Mozart example, there is a descending “5-line” over the course of the phrase.

Have a look at Brahms’s op.118, Intermezzo in A minor